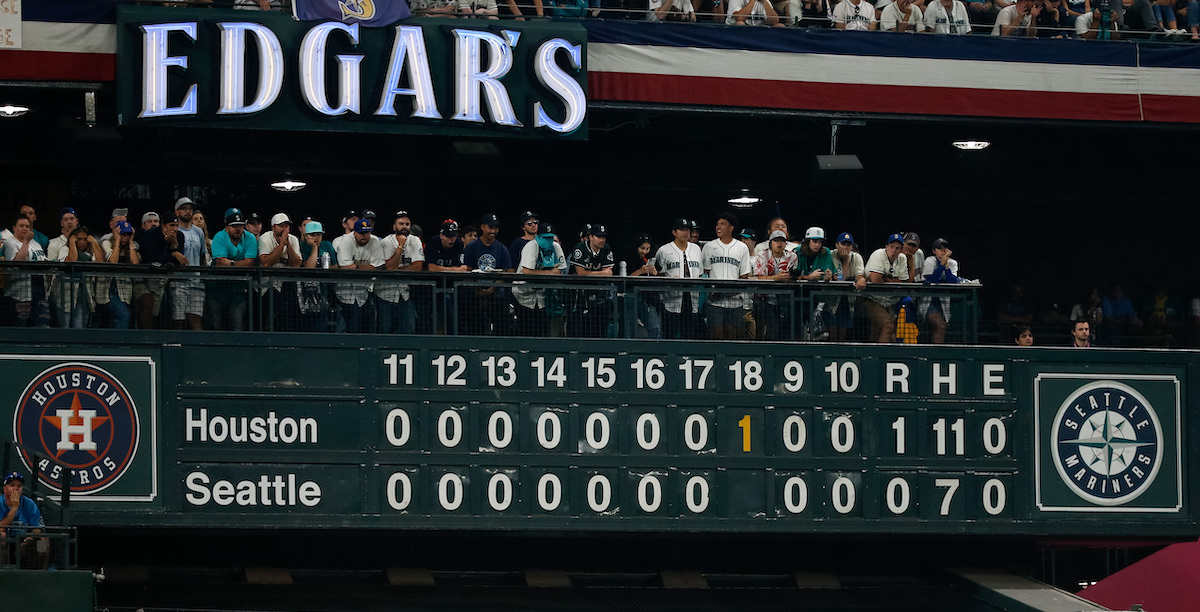

House groups don’t win sufficient in further innings. It’s one of the vital persistent mysteries of the final 5 years of baseball. Earlier than the 2020 season, MLB modified the additional innings guidelines to begin every half of every further body with a runner on second base. (This solely happens through the common season, which suggests the 18-inning ALDS tilt between the Mariners and the Astros within the image above didn’t really function zombie runners, however the shot was too good to move up.) They did so to minimize the damage and tear on pitchers, and maintain video games to a manageable size. Nearly actually, although, they weren’t planning on diminishing house area benefit whereas they have been at it.

Lately, Rob Mains of Baseball Prospectus has extensively documented the plight of the house group. Connelly Doan measured the incidence of bunts in further innings and in contrast the noticed charge to a theoretical optimum. Earlier this month, Jay Jaffe dove into the small print and famous that strikeouts and walks are a key level of distinction between regulation frames and bonus baseball. These all clarify the differing dynamics current in extras. However there’s one query I haven’t seen answered: How precisely does this work in follow? Are house groups scoring too little? Are away groups scoring an excessive amount of? Do house groups play the conditions improperly? I got down to reply these questions empirically, utilizing all the information we’ve on further innings, to get a way of the place concept and follow diverge.

The speculation of additional inning scoring is comparatively easy. I laid it out in 2020, and the maths nonetheless works. You may take a run expectancy chart, begin with a runner on second and nobody out, and work out what number of runs groups rating in that scenario generally. If you wish to get fancy, you’ll be able to even discover a distribution: how usually they rating one run, two runs, no runs, and so forth. For instance, I can inform you that from 2020 to 2025, excluding the ninth inning and additional innings, groups that put a runner on second base with nobody out went on to attain 0.99 runs per inning.

That’s the related scenario that highway groups face in extras. They’ve a runner on second with nobody out to begin the inning, and so they’re attempting to attain runs. They’ve been pretty profitable at it, scoring 1.00 runs per inning throughout the 1,354 further innings in my pattern. That’s statistically indistinguishable from the general main league common. Break it down by frequency of outcome, and you continue to can’t see a lot distinction:

Runs Scored After Man on Second, No Out

| Scoring | Regulation | High of Extras |

|---|---|---|

| 0 Runs | 45.6% | 47.5% |

| 1 Run | 31.1% | 28.3% |

| 2 Runs | 11.7% | 11.1% |

| 3+ Runs | 11.6% | 13.1% |

The distinction in run-scoring frequency is true on the border of statistical significance, however the route is sensible. Visiting groups put up precisely one run barely much less regularly than a naive run expectation, which tracks with how further inning video games work. As Jaffe’s analysis demonstrates, strikeouts improve in further innings. The defensive positioning and technique in further innings prioritizes sustaining a tie; groups play the infield in and attempt to make performs on the plate at the next charge within the tenth inning than within the second, naturally sufficient. For probably the most half, although, visiting groups in extras are scoring precisely how we’d count on based mostly on the broad efficiency of the league as an entire over the previous half decade.

With that knowledge in hand, we are able to deal with the house group. Not like most analyses, we already know what we’re going to seek out right here in broad strokes. Visiting groups convert the runner on second base into runs on the identical charge they do in regulation innings. House groups should not be, what with them profitable fewer further inning video games than you’d count on and all. However how and the place do they arrive up brief? The info needs to be our information.

Take into account the scenario the place the visiting group fails to attain within the prime half of the inning. A naive expectation, fully ignoring the actual methods every group may deploy in extras, means that the house group would rating round 55% of the time – one minus the possibility of scoring no runs after beginning with a runner on second and nobody out. What has really occurred? The house group has scored about 56.5% of the time. What number of runs they rating – and thus, the run expectancy – is pointless. In the event that they rating on this situation, that’s sufficient to win. Right here, not less than, house groups are performing precisely as you’d count on from the way in which they rating runs throughout regulation innings.

Let’s transfer on. What occurs when the house group begins the underside half of an additional inning down by a run? Utilizing our naive possibilities from up above, you’d count on them to attain zero runs and thus lose 45% of the time. As a substitute, they’re arising empty 49.1% of the time. You’d count on them to attain one run and tie the sport, sending it to a different body, an extra 31% of the time. In actuality, although, groups solely scratch out that tying run 29% of the time. Lastly, you’d count on house groups to attain twice and win about 23% of the time, however they’re doing so solely 22% of the time. In different phrases, after the visiting group will get forward within the prime of the inning, they shut the sport out extra regularly than you’d count on based mostly on the league’s total manufacturing with a runner on second base and nobody out.

That hole explains a considerable portion of the house area drawback related to the brand new further innings rule. House groups have began the underside half of an additional body with a one-run deficit 389 occasions underneath the brand new guidelines. In the event that they scored the identical means they do in regulation, they’d find yourself with 177 losses, 91 wins, and 121 occasions the place they re-tie the sport and ship it to an extra further body. As a substitute, they’ve racked up 191 losses, 86 wins, and 112 occasions scoring a run and retaining the sport going. That web shortfall of 19 video games – 14 extra losses and 5 fewer wins – is about two share factors of profitable share throughout your entire inhabitants of additional inning video games. Per Mains, house groups gained at a 49.3% clip in extras from 2020 by means of 2024, as in comparison with a 52.2% charge underneath the traditional further innings guidelines.

If we’re searching for specifics, it might behoove us to zoom in on why groups can’t money in that zombie runner usually sufficient to tie the sport. That’s the sticking level on this evaluation. In regulation innings, that runner scores way more regularly than in extras. It’s not onerous to know why. The protection is completely different, in spite of everything. With a runner on third and one out, the defensive group has a big selection of choices. They might convey the infield in and pitch for a strikeout. They might concede the run. They might deliberately stroll somebody to arrange a double play.

Within the early innings, groups nearly all the time concede the run in trade for a method that’s almost certainly to report some kind of out, run-scoring or in any other case, which appears smart. Enjoying to the rating doesn’t make a lot sense when many of the sport continues to be left to play. Within the later innings, nonetheless, most defenses will swap ways, prioritizing lead preservation over the very best probability of producing an out.

For example, contemplate house groups enjoying protection within the prime of an extra-inning body. When a runner reaches third with nobody out, the visiting group scores 82% of the time. When a runner is on third with one out, they rating 65% of the time. These numbers are roughly according to what occurs in the identical scenario in regulation; the visiting group scores a hair much less usually in extras than in regulation, however throughout the margin of error. Possibly the protection is expending effort attempting to stop that one run, however the offense is expending an equal quantity of effort attempting to attain it (working on contact, shortening swings in pursuit of balls in play, and so on.), and the web result’s that visiting groups money in runs at primarily the identical charge whether or not they’re enjoying in regulation or extras.

Check out the house facet of issues, then again, and also you’ll see a distinction. When the house group places a runner on third with nobody out in a tie sport in extras (small pattern alert), they solely money in that runner 75% of the time. A runner on third with one out? They rating 58% of the time. Down a run, these numbers are roughly the identical. The pattern is small on all of those, in fact, however there’s no denying what has occurred to this point. That’s meaningfully decrease than you’d count on from the scoring atmosphere that prevails in regulation. In different phrases, house groups aren’t pretty much as good at cashing in runners from third in further innings, whether or not you’re evaluating them to regulation baseball or to visiting groups in extras.

Why is that? Defensive positioning and technique is my greatest guess. When the visiting group faces a runner on third with nobody out in a tie sport in further innings, they haven’t any selection: They’re stranding that runner or the sport is over. You may take much more dangers along with your again in opposition to the wall. You may pitch for strikeouts, deliberately stroll hitters you don’t need to face, play the infield and outfield ridiculously shut, attempt to throw out the runner at house even when it’s an extended shot, and even herald your greatest strikeout pitcher to tilt the scales in your favor. It’s not fairly the identical once you’re up a run, however groups are nonetheless keen to promote out to cease a run from scoring in that scenario, way more so than within the prime half of the inning or earlier within the sport.

In reality, this aggressive defensive posture is nothing new. From 2010 by means of 2019, to select a pre-zombie-runner pattern, house groups have been equally inept at getting a runner house from third base in further innings – or if you happen to’d desire, defensive squads have been equally good at stopping that run from scoring. The one motive it’s extra noticeable in house area benefit now’s as a result of we’re seeing these conditions extra usually. Within the previous days, getting a runner on third base with nobody out in further innings was vanishingly uncommon, and getting a runner there with one out wasn’t precisely widespread. Now, it’s nearly a given.

Stated one other means, house groups have all the time been at a drawback, relative to their regulation profitable share, in further innings. Mains’ analysis bears that out, and I’ve regarded into it earlier than with related findings. That’s partially due to a scenario the place they’ve traditionally carried out worse than the visiting group: scoring a runner from third with lower than two outs. That scenario occurs extra regularly now than it used to. It’s a traditional unintended consequence – nobody thought an excessive amount of about house groups’ underperformance in these spots as a result of it nearly by no means got here up. That imbalance simply didn’t matter a lot with out an computerized runner in place. Put somebody on base to begin the body, although, and changing runners into runs begins to matter much more.

In case you’re like me, there’s one thread nonetheless nagging at you. If defenses are so good at stopping runners from third from scoring, why don’t we see it within the outcomes I quoted for house group profitable share when the visiting group fails to attain? It’s as a result of we’re lacking a variable: bunts.

See, house groups are much less environment friendly at changing runners on third into runs, however in tie video games, they get runners to 3rd base with one out extra regularly than you’d count on. They accomplish that by bunting. Positive, Doan’s analysis discovered that groups weren’t bunting sufficient in further innings, nevertheless it additionally demonstrated, far past the shadow of a doubt, that groups bunt way more than they do in regulation innings. Beginning the underside of a tied further inning with a bunt is a profitable play. It will increase win likelihood meaningfully from a naive estimate. It simply so occurs that it will increase win likelihood by sufficient that it offsets the following challenges that the house group has driving that run house.

I discover this puzzle fascinating. It simply feels mistaken that house groups have a drawback in further innings, the very time when attending to see what your opponent did first ought to matter most. However because it seems, house groups have all the time struggled, on a relative foundation, to money in “straightforward” runs in extras. The brand new further inning rule creates extra possibilities to money in straightforward runs. Identical to that, you find yourself with a mysterious consequence – house groups aren’t profitable sufficient. The important thing issue that creates this counterintuitive house area drawback has been round for a very long time. We simply by no means seen it earlier than the zombie runner turned “Are you able to get that dude house?” from an extra-innings afterthought to a high-frequency problem.

This text has been up to date to right the speed at which each house and away groups rating with a runner from third, correcting an earlier transcription error.