Watch this play. What do you discover?

Right here’s what I see: Brooks Lee lofts a tender fly ball 248 toes from house plate. Chandler Simpson circles it however loses a little bit of momentum by the point it lands in his glove. Twins third base coach Tommy Watkins sends the not-particularly-fast Trevor Larnach (18th-percentile dash velocity). Shallow fly ball, gradual runner, shut play on the plate — Larnach slides in simply forward of the throw. It’s an thrilling sequence, and I’ve missed an essential a part of it.

Throughout a chat on the Saberseminar convention two Saturdays previous, Josh Kalk, an assistant normal supervisor with the Minnesota Twins, went by way of this similar train, exhibiting this Lee sacrifice fly, after which asking the viewers: What do you discover? He needed to speak concerning the play behind the play. Particularly, he needed to speak about this man:

That’s Carlos Correa, studying the throw and scampering off to second base. Whether or not groups capitalize on these path runner alternatives, Kalk urged, issues greater than most individuals notice.

There it was, an ideal submit concept introduced on a platter. How usually do groups make the most of potential path runner advances? Which groups do it finest? And what kind of impression are we speaking about right here?

I figured the variations between groups can be marginal at finest. Baserunning margins, even within the broadest sense, are fairly slim. By Statcast’s Baserunning Run Worth leaderboard, the unfold between the very best workforce (the Brewers) and the worst (the Rockies) is 20 runs, or roughly two wins. (Our analogous BsR statistic sees the hole as roughly the identical.) In comparison with hitting, pitching, and even fielding, baserunning is kind of the ugly duckling of public baseball evaluation, and I believe the slender variations between groups assist to clarify why.

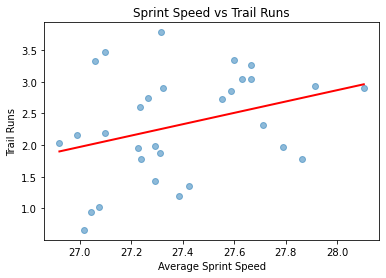

Another excuse: A lot of the variation between these groups may be defined by a single apparent variable. On the whole, quick groups are usually good baserunning groups. The BsR-leading Brewers, for instance, are additionally the second-fastest workforce within the majors. The connection between dash velocity and baserunning worth is comparatively robust — because the daybreak of the Statcast period (2015), there’s an r-squared of 0.307 between workforce dash velocity and a blended model of FanGraphs BsR and Statcast baserunning worth:

However even after factoring in dash velocity, there’s nonetheless a very good chunk of variation to account for. Take the poor Rockies. Their dash velocity is an identical to the Brewers’; in addition they rank useless final in each BsR and Baserunning Run Worth. As Juan Soto and Josh Naylor have proven this season, velocity isn’t the whole lot relating to working the bases with talent. It takes instincts, good reads, split-second selections, and high quality teaching on the corners. It’s extra than simply zooming from base to base.

Take the Lee sacrifice fly from the lede, the place the slow-footed Correa superior to second on the throw. There’s a essential a part of the play the place Correa should make the choice to both break for second or keep put at first. It’s proper round right here, when the third baseman Junior Caminero has to make a equally troublesome split-second resolution:

If Caminero cuts off the throw and Correa is frolicked in no man’s land, that’s the tip of the inning. However he strikes his glove on the final second, letting the throw sail house. Given how shut the play was on the plate, I believe Caminero made the suitable name. However even perhaps higher was Correa’s learn — Caminero was in good place, and Correa managed to take the bottom anyway.

Not all path runner situations are this difficult; there are occasions when even probably the most oafish of baserunners can coast into second. If it was principally coasting oafs, you’d anticipate all groups to exhibit roughly the identical talent stage. However that doesn’t turn into the case.

To collect my information, I relied on the knowledge of the official scorers. There isn’t any simple approach to account for path runners, as I’ve discovered slightly painfully over the past couple of weeks. Baseball Savant gives a .csv file of each single pitch thrown within the common season (shout out Baseball Savant), however these information don’t embody a lot baserunning info in tabular kind — solely the place the runners began, actually, and the id of stated runners. An R operate produces the following base state of a given play (due to Robert Frey for pointing this out), however there’s no approach to decide whether or not the runner on second bought there as a result of he hit a double or as a result of he hit a single and superior to second as a path runner.

This additionally required me to set a transparent definition of who, precisely, is a “path runner.” First, I eradicated all house runs (clearly), triples (since a triple will all the time clear the bases, and the hitter can’t rating with out an error), and groundball outs (completely different type of state of affairs). That left all singles and doubles with a minimum of one runner on base, in addition to all fly balls with a minimum of two runners on base, as attainable path runner situations.

For the singles and doubles, I made the maybe controversial resolution to name the batter the path runner in all instances. My logic was one thing like: If anyone hit a single up the center with runners on the corners, the man on third will rating simply in 99% of instances. He’s now not the protection’s concern. It’s the man on first who turns into the lead runner, and the protection focuses on stopping his advance, making the batter the path runner.

The logic was a bit of completely different for fly outs. If there was a couple of runner on base, I outlined the path runner because the runner furthest from house plate. For instance, if the bases had been loaded, the path runner can be on first base. In all instances, although, I restricted the variety of attainable path runners on a given play to 1.

To determine these conditions, I used the Gameday descriptions. If the Gameday description stated the runner singled after which superior to second, I thought-about him a path runner. (An instance: “Roman Anthony singles on a groundball to heart fielder Jung Hoo Lee. Jarren Duran scores. Roman Anthony to 2nd.”) Identical with doubles the place the runner superior to 3rd. Fly ball outs had been a bit of trickier. If the path runner’s identify appeared wherever within the description, I counted that as a path runner advance. (If the runner stays put, they’re not talked about; they’d solely seem within the description in the event that they superior a base or bought thrown out, and I eradicated double performs from the dataset.)

As of August 25, by these outlined parameters, there had been solely 501 path runner developments throughout the complete season. (I’ll admit, that stunned me.) So which groups do it finest? And the way a lot does it matter? First, I counted the whole variety of developments for every workforce. Right here’s the record:

Path Runner Advances

| Staff | Path Runner Advances |

|---|---|

| Detroit Tigers | 28 |

| St. Louis Cardinals | 26 |

| Toronto Blue Jays | 25 |

| Miami Marlins | 23 |

| Arizona Diamondbacks | 23 |

| Milwaukee Brewers | 22 |

| Cincinnati Reds | 21 |

| San Diego Padres | 20 |

| Tampa Bay Rays | 20 |

| Chicago Cubs | 19 |

| Boston Purple Sox | 18 |

| Los Angeles Dodgers | 18 |

| Cleveland Guardians | 18 |

| San Francisco Giants | 18 |

| Kansas Metropolis Royals | 17 |

| Philadelphia Phillies | 16 |

| Baltimore Orioles | 16 |

| Texas Rangers | 15 |

| Colorado Rockies | 15 |

| Pittsburgh Pirates | 15 |

| Chicago White Sox | 14 |

| New York Mets | 14 |

| New York Yankees | 13 |

| Houston Astros | 12 |

| Athletics | 11 |

| Los Angeles Angels | 11 |

| Washington Nationals | 10 |

| Minnesota Twins | 9 |

| Seattle Mariners | 9 |

| Atlanta Braves | 5 |

Supply: Baseball Savant

However not all developments are created equal. A runner taking third with no outs will increase the run expectancy greater than a runner heading to second with two outs. To determine the worth of every development, I calculated the run expectancy for every base-out state following the conclusion of the play, then backtracked to calculate what that run expectancy would’ve been had the path runner not superior. The delta between these two figures produces a crude run worth. Add up all of the the run expectancy deltas, and you’ve got one thing like a run worth leaderboard for path runners alone. Right here’s what that appears like:

Path Runner Runs Gained

| Staff | RE Gained |

|---|---|

| Detroit Tigers | 3.786 |

| St. Louis Cardinals | 3.474 |

| Arizona Diamondbacks | 3.353 |

| Toronto Blue Jays | 3.327 |

| Cincinnati Reds | 3.271 |

| Boston Purple Sox | 3.05 |

| Miami Marlins | 3.039 |

| Milwaukee Brewers | 2.934 |

| Kansas Metropolis Royals | 2.907 |

| Philadelphia Phillies | 2.898 |

| Chicago Cubs | 2.856 |

| San Diego Padres | 2.739 |

| Tampa Bay Rays | 2.736 |

| Los Angeles Dodgers | 2.609 |

| Baltimore Orioles | 2.317 |

| San Francisco Giants | 2.189 |

| Chicago White Sox | 2.157 |

| New York Mets | 2.035 |

| Cleveland Guardians | 1.981 |

| Pittsburgh Pirates | 1.973 |

| Texas Rangers | 1.948 |

| Houston Astros | 1.875 |

| New York Yankees | 1.774 |

| Colorado Rockies | 1.774 |

| Athletics | 1.429 |

| Washington Nationals | 1.351 |

| Los Angeles Angels | 1.195 |

| Seattle Mariners | 1.023 |

| Minnesota Twins | 0.947 |

| Atlanta Braves | 0.657 |

Supply: Baseball Savant

Calculated as delta between post-play base/out run expectancy and run expectancy if path runner had not superior.

Maybe that’s all a bit of underwhelming. The hole between the Tigers and the Braves — a bit of over three runs — isn’t particularly spectacular. However possibly that’s the fallacious lens. In an excellent world, it wouldn’t be a run expectancy delta, however a win expectancy delta. Adjustments in win expectancy level extra to the substance of Kalk’s feedback: On a given play and recreation stage, a runner advancing can matter a ton.

Calculating win expectancy adjustments on the play stage is difficult — maybe a job for the following article — however we are able to have a look at one consultant instance to point out the potential impression of a path runner development on win expectancy. In late August, two American League Wild Card contenders had been locked in a good contest. The Rangers had been trailing the Guardians by one; the speedy Wyatt Langford stood on second base. On the primary pitch, Corey Seager ripped a clear line drive to heart discipline. The Guardians’ heart fielder, Angel Martínez, uncorked an enormous throw and practically gunned Langford down on the plate:

If Seager remains to be standing on first after this throw, the Rangers’ odds of successful this recreation are 70.8%, in keeping with Tom Tango’s win expectancy spreadsheet. As an alternative, he correctly tracked the throw (not that robust of a learn, finally — Martínez launched that factor) and elevated his workforce’s odds of successful by 10 proportion factors. With a runner on second and no outs, the Rangers’ odds of successful at this level had been 80.7%. Seager scored on the following pitch, jogging house after Joc Pederson scorched a double into the hole.

Curiously, “runs gained from path runners advancing” doesn’t seem to map onto workforce dash velocity as neatly because it does to BsR. The r-squared this season between these two variables is simply 0.11, a weaker relationship than dash velocity has ever needed to BsR in the course of the Statcast period:

Maybe this explains why Kalk’s consideration is concentrated on this ostensibly marginal a part of the sport. It doesn’t take a workforce of Trea Turners to prime the path runner leaderboards; any workforce can decide up a pair additional runs over the course of a season — and maybe even swing the end result of some video games — with correct consideration to those free bases. When aggressive edges are few and much between, a penny mendacity on the sidewalk begins to seem like a $20 invoice.